Decoding LoRA: A Comprehensive Summary on Low-Rank Adaptation

Recently, I came across an intriguing article on low-rank techniques employed in Large Language Models (LLM) specifically focusing on LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. Here’s a succinct summary of the key concepts, along with additional discussions.

Problem

Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) tackles challenges linked to fine-tuning large language models, typified by models like GPT-3. LoRA addresses:

-

Resource-Intensive Fine-Tuning: Traditional fine-tuning of large language models demands significant computational resources, resulting in high costs and storage requirements due to adjustments in numerous parameters.

-

Inefficiencies of Existing Methods: Prior strategies, such as adapter layers and prompt optimization, have limitations. Adapter layers may introduce inference latency, and direct prompt optimization, as in prefix tuning, poses optimization challenges and constraints on sequence length.

-

Storage and Deployment Challenges: Full fine-tuning of large models presents issues in memory and storage, hindering practical deployment. LoRA seeks to reduce trainable parameters, addressing these concerns.

LoRA

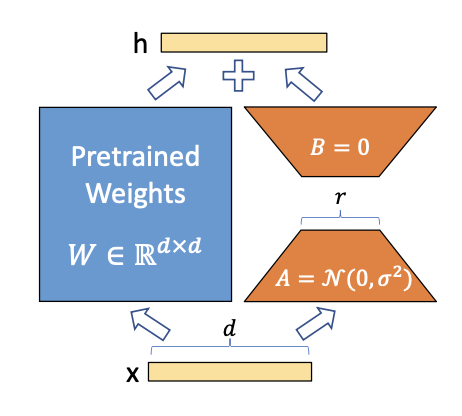

In LoRA, adapting a pre-trained weight matrix $\mathbf{W}_0 \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times k}$ involves a low-rank decomposition:

\[\mathbf{W}_0 + \Delta \mathbf{W} = \mathbf{W}_0 + \mathbf{BA},\]where $\mathbf{B} \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times r}$, $\mathbf{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{r \times k}$, and $r \ll \min(d, k)$, represent reduced dimensionality, input dimension $d$, and output dimension $k$, respectively.

The challenge is to determine the optimal values for $\mathbf{B}$ and $\mathbf{A}$ that minimize the loss on the target task while significantly reducing the number of trainable parameters. This problem is critical for efficient adaptation without sacrificing task performance.

LoRA initializes these matrices with the following approach:

Matrix $\mathbf{A}$:

- Random Initialization: $\mathbf{A} \sim N(\mathbf{0}, \sigma\mathbf{I})$. This randomness introduces diversity in the adaptation process, helping the model explore different solutions.

- Meaningful Initialization: Task-specific meaningful initialization if applicable.

Matrix $\mathbf{B}$:

- Zero Initialization: $\mathbf{B}$ is initialized with zeros. This choice may be driven by the idea that, at the beginning of training, no specific adaptations are needed ($\mathbf{BA}$ is effectively zero).

- Other Initialization Schemes: Explore alternative initialization schemes based on task characteristics.

The illustration in Fig. 1 depicts LoRA. Additionally, a scaling factor $\alpha_r > 0$ is applied during optimization to manage hyperparameters, reducing the need for extensive tuning.

Why LoRA?

Efficiency of LoRA:

- Reduced Trainable Parameters: The low-rank constraint significantly reduces trainable parameters, especially beneficial for large language models, enhancing computational efficiency during training.

- Memory and Storage Savings: Low-rank decomposition substantially reduces memory and storage needs, providing significant savings, crucial for large architectures like GPT-3.

- Generalization of Fine-Tuning: LoRA allows training a subset of parameters without requiring full-rank updates, offering flexibility in adaptation without full computational demands.

- No Additional Inference Latency: Stored matrices $\mathbf{W}_0$ and $\mathbf{BA}$ enable seamless task-switching during deployment without introducing latency, crucial for real-time applications.

- Versatility in Deployment: LoRA’s efficiency facilitates creating models with lower computational demands, allowing cost-effective task-switching by swapping only LoRA weights.

Note that the supplement provides additional insights, including experiments on low-rank matrices and observations related to the correlation between LoRA modules, the impact of rank $r$ on GPT-2, the relationship between $\mathbf{W}$ and $\Delta\mathbf{W}$, and the amplification factor. This factor gauges the emphasis on task-specific features during adaptation, offering valuable insights into the significance of specific directions for achieving optimal performance on targeted tasks, with a higher amplification factor indicating a greater emphasis on critical features in the adaptation process.

Conclusion

LoRA introduces a transformative paradigm for fine-tuning large language models, emphasizing efficiency in reducing trainable parameters through low-rank parametrized update matrices. Leveraging the low intrinsic dimensionality of pre-trained models, LoRA adapts them for specific tasks while preserving or enhancing performance. Applicable to various dense layers, particularly in Transformer language models, LoRA showcases consistent outperformance across models and tasks. Besides superior performance, LoRA significantly reduces memory and storage usage, offering a practical advantage for large-scale language models. Despite challenges in batching inputs, its simplicity, versatility, and empirical advantages position LoRA as a compelling and resource-efficient strategy for language model adaptation in real-world applications.

Further Discussion

While LoRA presents a promising approach to fine-tuning large language models, several open questions warrant exploration:

- Dynamic Rank Adaptation:

- Investigate techniques for dynamically adapting the rank parameter $r$ during the training process. This exploration could enhance LoRA’s adaptability to varying complexities of tasks over time.

- Enhanced Initialization Strategies:

- Further research into initialization strategies for matrices $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ could contribute to improved convergence and overall performance. Exploring methods that leverage covariance matrix estimation in statistics may offer a more informed and effective approach to initialization.

- Interpretability and Explainability:

- Develop techniques to enhance the interpretability and explainability of LoRA-adapted models. This effort would contribute to better understanding the impact of low-rank adaptations on model behavior, aiding model transparency.

Leveraging Covariance Matrix Estimation for Initialization

Integrating covariance matrix estimation into LoRA’s initialization strategies holds substantial potential for enhancing the robustness and efficiency of the adaptation process. By leveraging statistical insights, we can address key aspects:

- Capturing Task-Specific Dependencies:

- Utilizing covariance matrices helps capture task-specific dependencies in both input and output spaces. This ensures that the low-rank matrices $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ are initialized in a manner aligning with the statistical properties of the data, fostering improved adaptation.

- Adaptation to Task Characteristics:

- By considering the covariance structure, initialization strategies become more adaptive to the specific characteristics of both the pre-trained model and the target task. This adaptability may lead to faster convergence during the adaptation process.

- Reducing Sensitivity to Initialization:

- Initializing matrices based on covariance matrices can reduce sensitivity to random initialization variations, offering a more stable and consistent performance across different runs.

Moreover, introducing hidden structure to the covariance matrix (e.g., using methods like SpatPCA with smoothing splines) can further enhance interpretability, providing insights into the low-rank representations for a better understanding of the adapted model.

In summary, leveraging covariance matrix estimation in LoRA’s initialization strategies offers a more informed and statistically grounded approach. This integration provides a structured method for capturing dependencies in both input and output spaces, ultimately enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of the adaptation process.